- So close to heaven

- Sun on the skin

- Topless as pure feeling of luxury

- People sat vis-à-vis each other

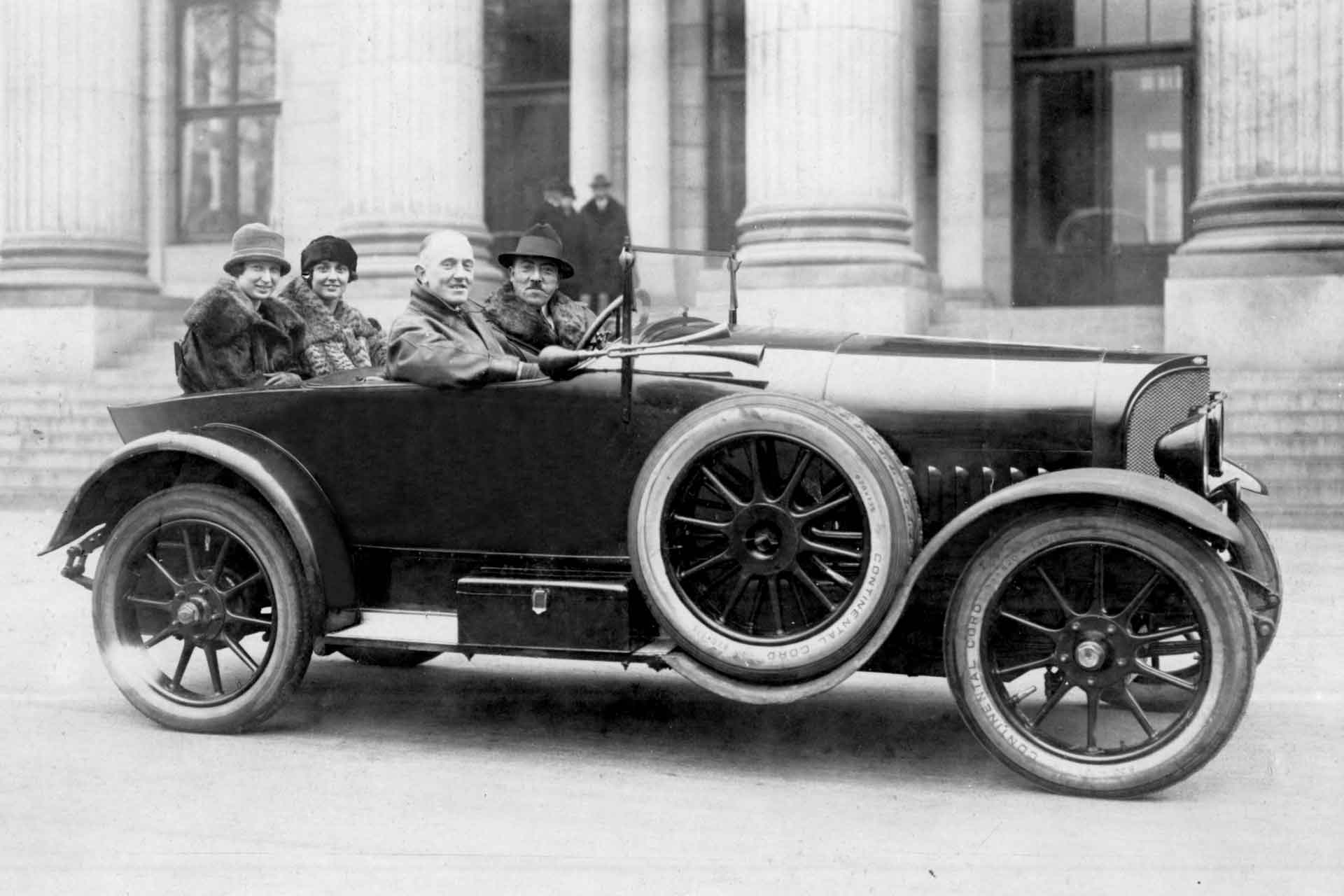

- Every body fits on a solid frame

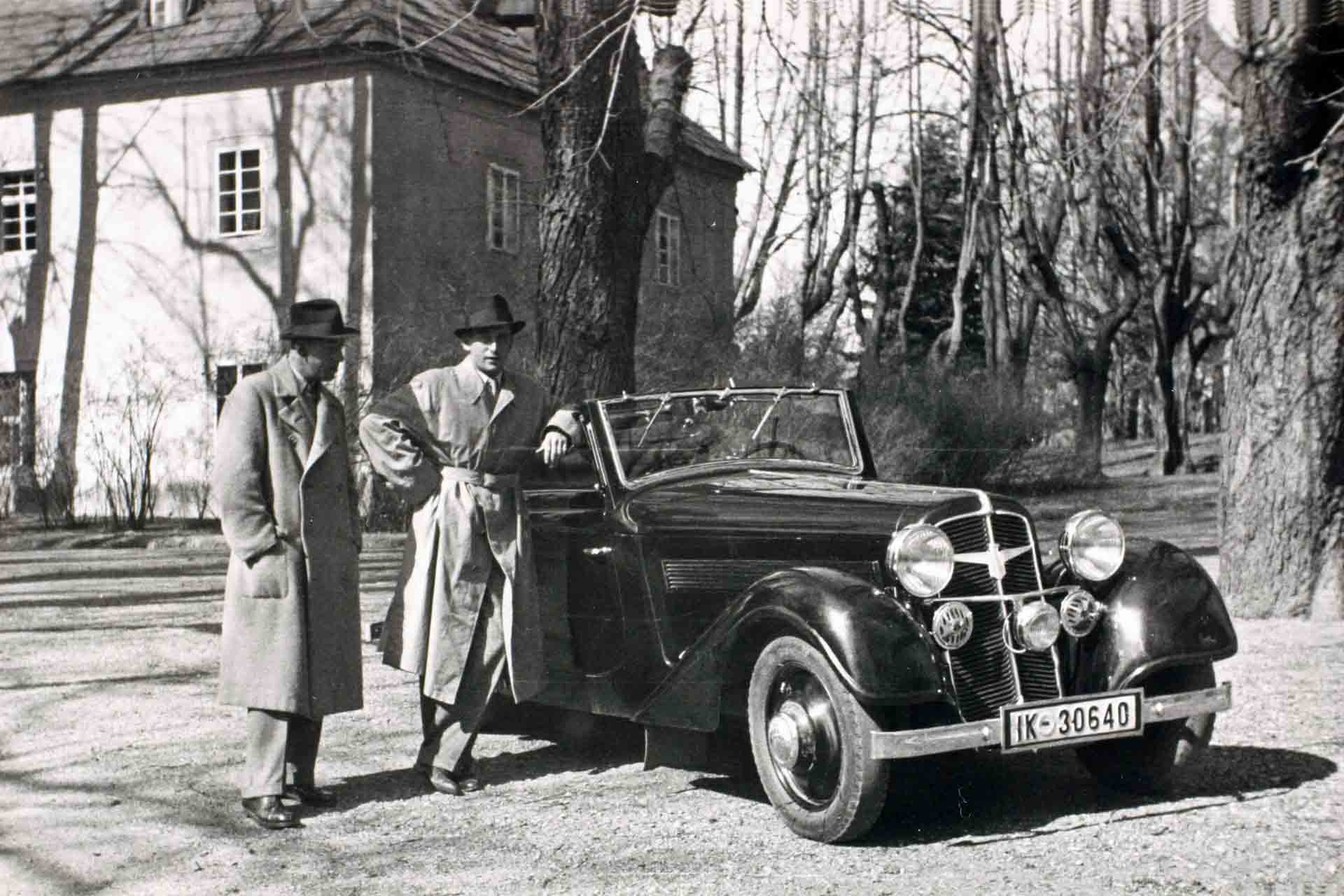

- The modern gentleman driver wants a roof over his head

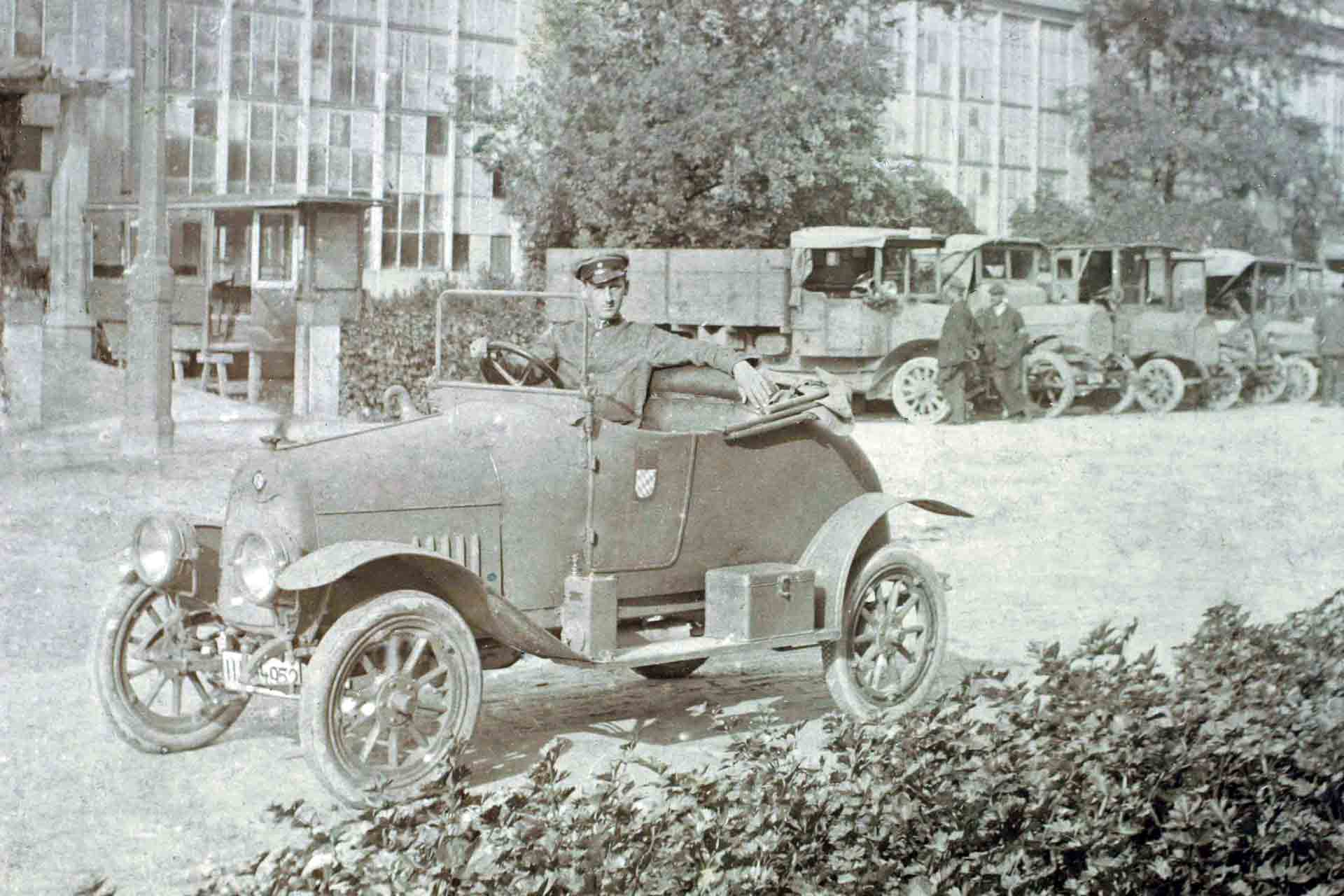

- The small roadster for the “dandy”

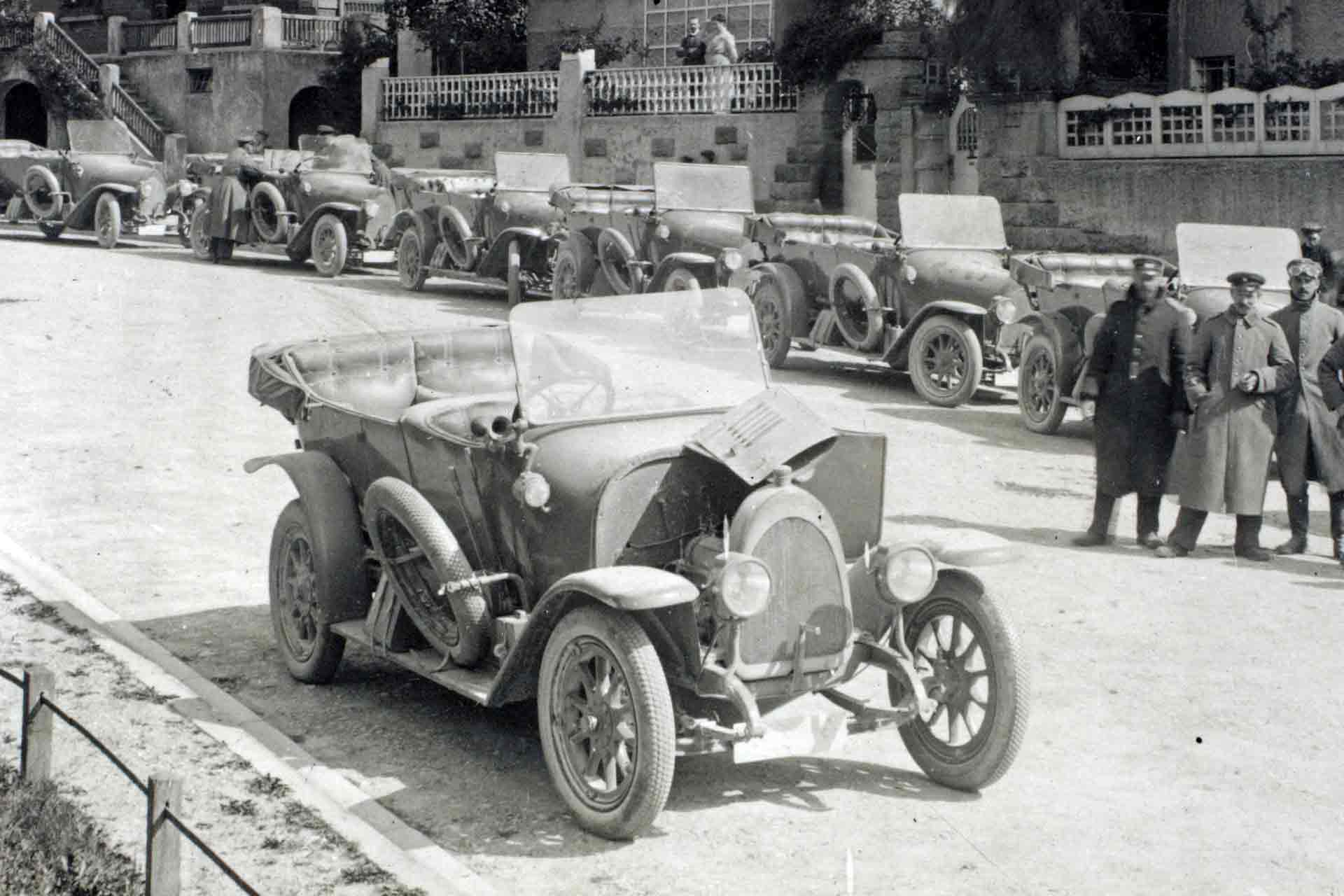

- With a military ulterior motive: off-road sporting events

- The system change in car body design

- Convertible sedan: neither fish nor fowl

Summer, sun, convertible

Feeling the sun. Watching the sun. Smelling the sun. And at the same time driving, traveling, cruising, speeding, dawdling, posing – whatever, in the sunshine. Alone, in company of two, three, or four, with a girlfriend, a boyfriend, mom, dad, the kids, grandpa, or grandma, but always topless. That’s a convertible. That is a car without a roof. That is beautiful, a pleasure, nature, power, that is sensual, that is dreamlike. Part 1 of the history of the convertible.

So close to heaven

A bit of Goethe, modified, perhaps? Here you go: Everything depends on the convertible. Oh, poor us! (loosely based on Gretchen, in “Faust”, who laments man’s urge for gold) For those who have a convertible don’t want to miss it. And those who don’t have one dream of it. In summer, in the sunshine. On lonely country roads, on serpentines in the mountains, along the dike, on the corniche on the Côte d’Azur, or along the Belgian North Sea coast between Knokke and De Panne, around Lake Constance, possibly also on the Kö in Düsseldorf or the Leopoldstraße in Munich, where everyone is watching you. Or on a third-rate side street in Brittany (or in the hinterland of Castrop-Rauxel), where no one sees you.

Sun on the skin

Seeing and being seen, that is important for some. Being alone with your loved one, not being caught by anyone, that’s important for others. Convertible rides can do so much: meeting your dream partner in a convertible, going on a picnic, relaxing on the way home from the most important contract signing ever, adding sound to the surroundings (in the past with a Kenwood with an equalizer, today with a Bose sound system), letting the V8 roar like a rutting deer or whispering as it glides along. It doesn’t matter if there are 70 or 700 hp under the hood – the convertible does something with you. You show yourself to everyone and you let yourself be celebrated, offensively, hey, look! It’s me, me and my car (and my girlfriend and my music)! Or vice versa: top down, but the tinted side windows up, lady and gentleman with sunglasses and camouflaged under a fine headscarf (she) and Prince Henry cap (he), the car as silver as his temples, as discreet as their appearance – oh please, don’t look, don’t recognize me, I want to enjoy my convertible, but not be recognized. So that no envy arises. The prototype of the roaring convertible may be the Lambo or Ferrari or Porsche, the prototype of the whispering convertible the Bentley or Maybach or Mercedes. The only thing they have in common is the folding roof and the crew’s desire to feel the sun on their skin. And that’s not a small amount of common ground!

[1] An all-time favorite: the Beetle Cabrio, here the last version 1303. It was available from the factory until January 10, 1980. (Photo: Volkswagen)

[2] Also an absolute classic: no convertible is more frequently on the road in Germany with a vintage car license plate than the Mercedes R 107. (Photo: Daimler-Benz)

Topless as pure feeling of luxury

Today, a convertible is pleasure and luxury alike. That wasn’t always the case. But it has been for three quarters of a century, since World War II. That was not only a major political turning point, but also an automotive one. So much changed after the war. The trendy styling was called pontoon shape. And the new designs were self-supporting bodies. The pontoon design, roughly speaking, just means modernity in visual appearance – of course, a body designer or engineer would disagree with that statement and offer an hour-long monologue. For the body superstructures, the change from the classical design (a body is bolted to a separate chassis) to the self-supporting superstructure (body and chassis as a unit, virtually the principle of the shell) means that there is no longer a choice of superstructures. The new designs after the war are either two- or four-door sedans or vans, i.e. station wagons without rear side windows. Convertibles are not among them. This is because convertibles are henceforth luxury items with low projected numbers of units to be produced. The large-volume manufacturers leave that to the external body builders. And ultimately, that’s exactly how it stayed until about 15 years ago.

[1] The open-top feeling comes in every price and performance class. The first Golf Cabrio was considered a girl’s car, but when Toni Rieger from Eastern Bavaria got his hands on it, it was almost as wide as it was long. (Photo: Toni Rieger)

[2] High class: the Mercedes 300 SL Roadster W 198/II from 1957, a high-priced classic. (Photo: afs)

[3] For those born on the bright side: the Bentley Continental Azur from 1997. (Photo: Bentley)

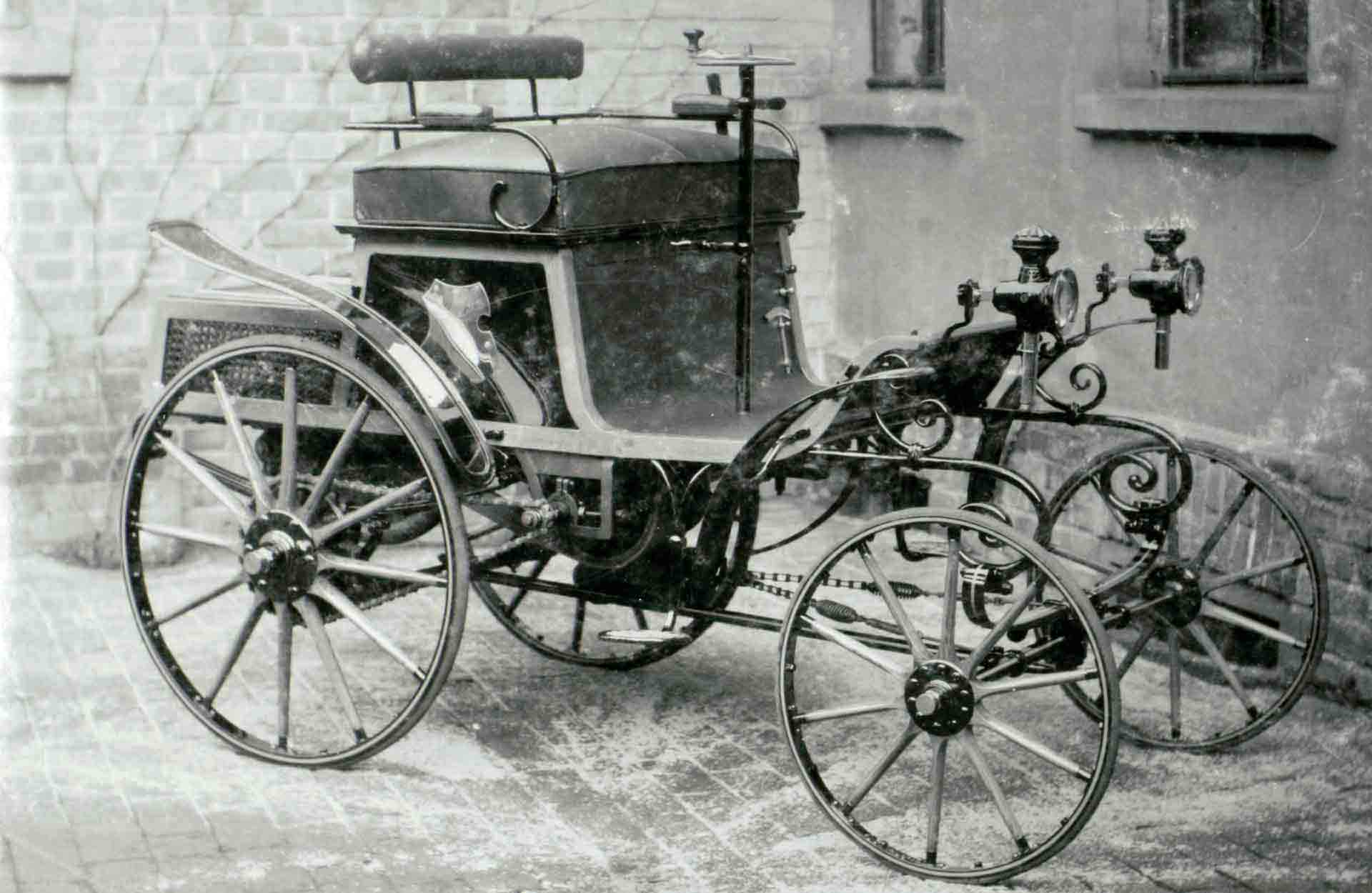

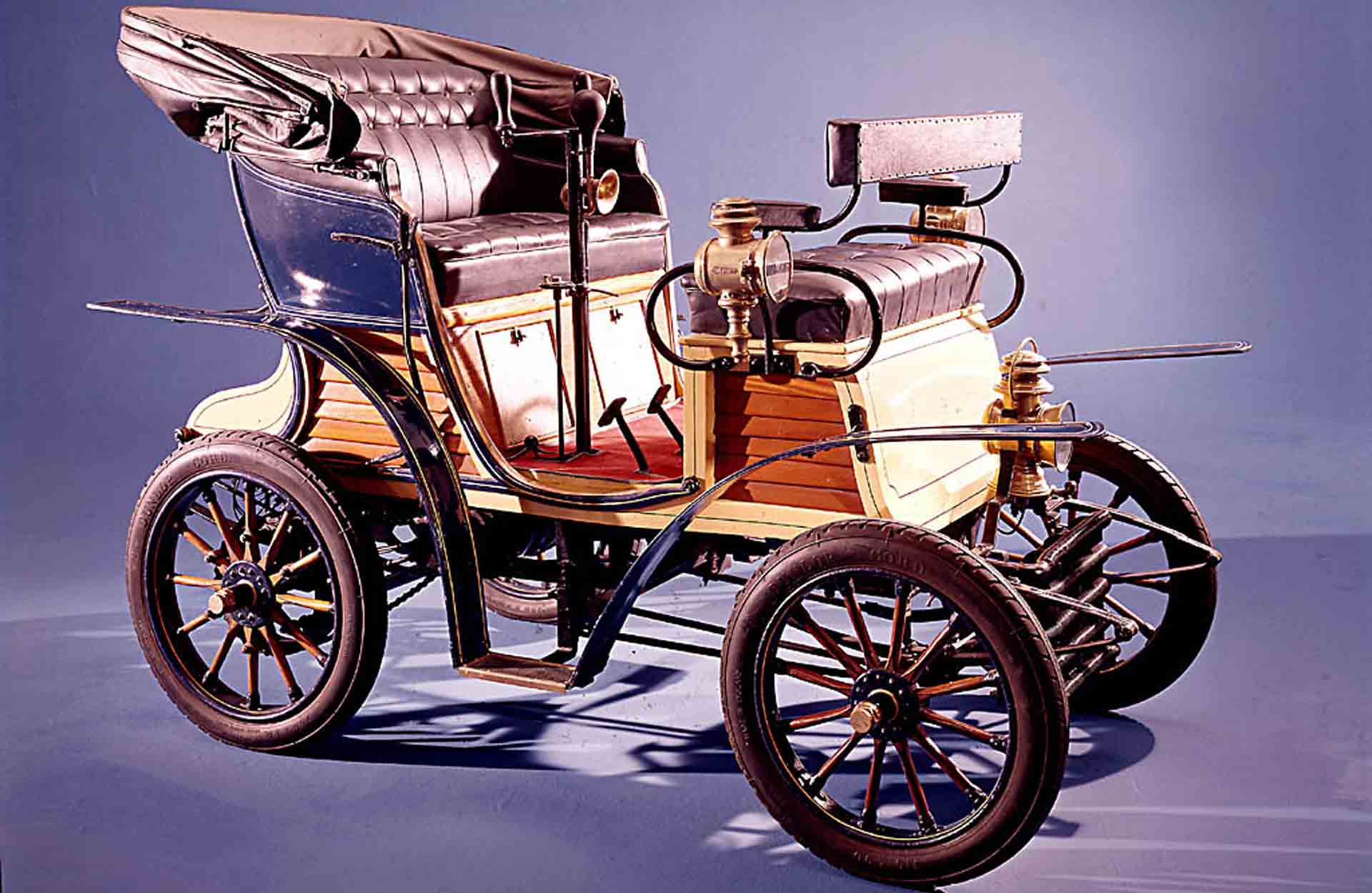

People sat vis-à-vis each other

In the beginning is the convertible. The first automobiles, created at the end of the 19th century, are open – as are most horse-drawn carriages, and their modern successor is the automobile. A rider on a horse has no roof over his head either. The body variants go by names that are unfamiliar today, such as Dos-à-Dos, Vis-à-Vis, or Tonneau – names from the days when carriages were built, and they indicate the seating arrangement of the passengers. Because not even that is as defined back then as it is today, where people sit next to and behind each other facing forward in the car. In the Vis-à-Vis, for example, people sit opposite each other – nomen est omen – while in the Tonneau, the driver sat “normally” and the passengers sat lengthwise to the direction of travel. Very curious from today’s point of view!

[1] Lutzmann motor car before Herr Friedrich Lutzmann and his inventory were taken over by Opel. Photo taken in Dessau in March 1898. (Photo: Daimler archive)

[2] The first cars are open: a Hoch 14/17 hp tonneau from 1904. (Photo: Matthias Schmidt)

[3] Passengers look at the driver, who sat on the back seat: a Fiat 3/12 hp from 1899. (Photo: Fiat archive)

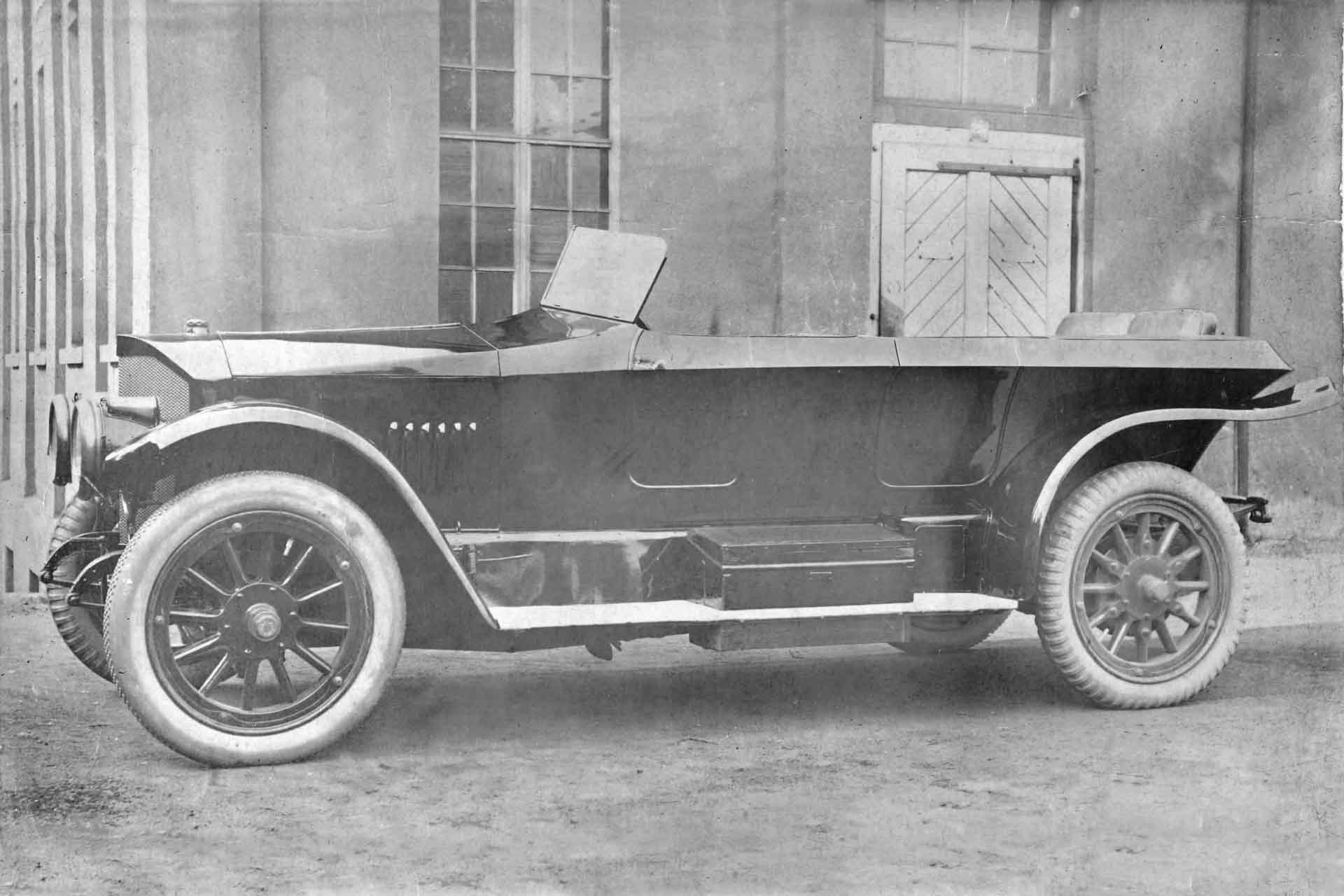

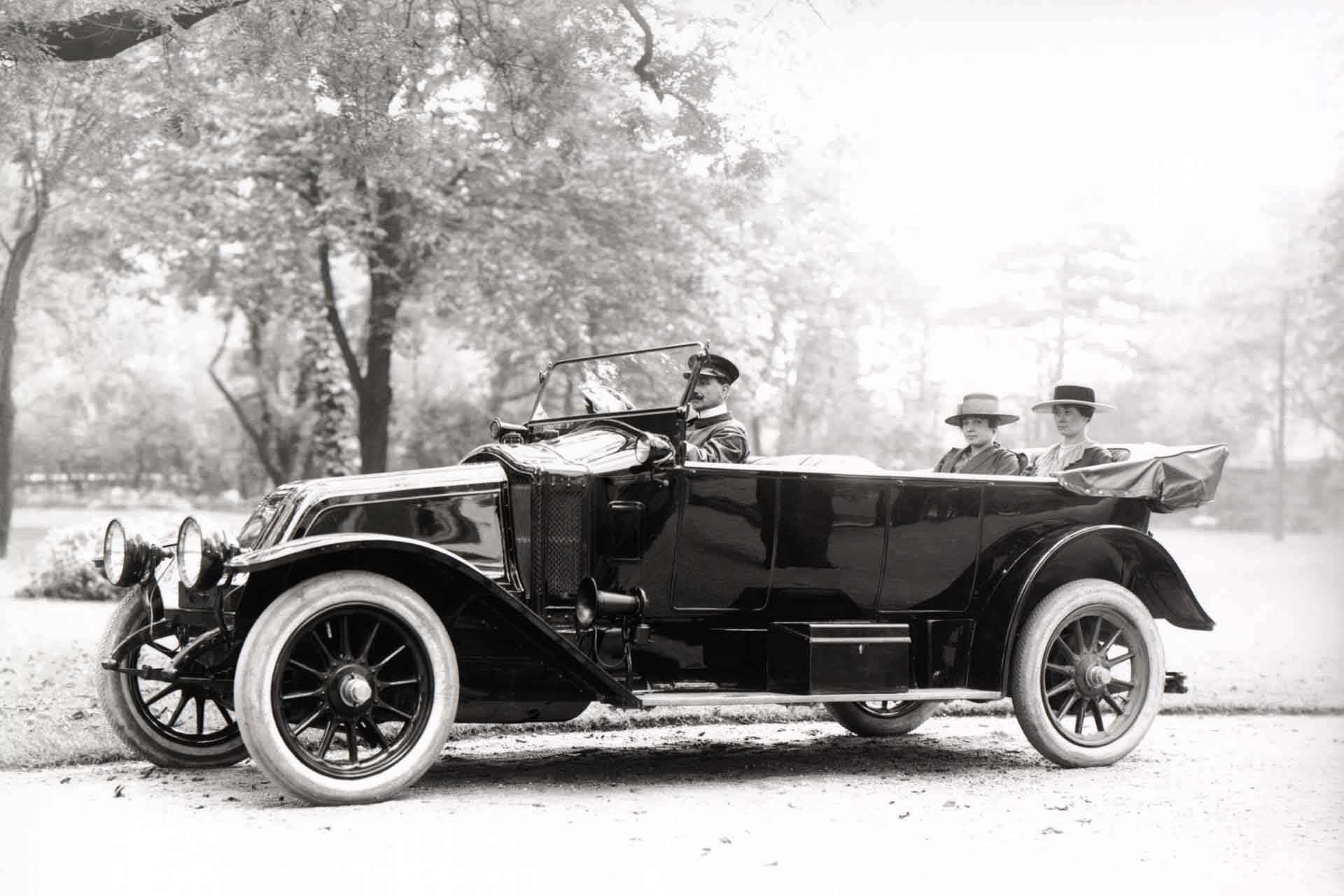

Every body fits on a solid frame

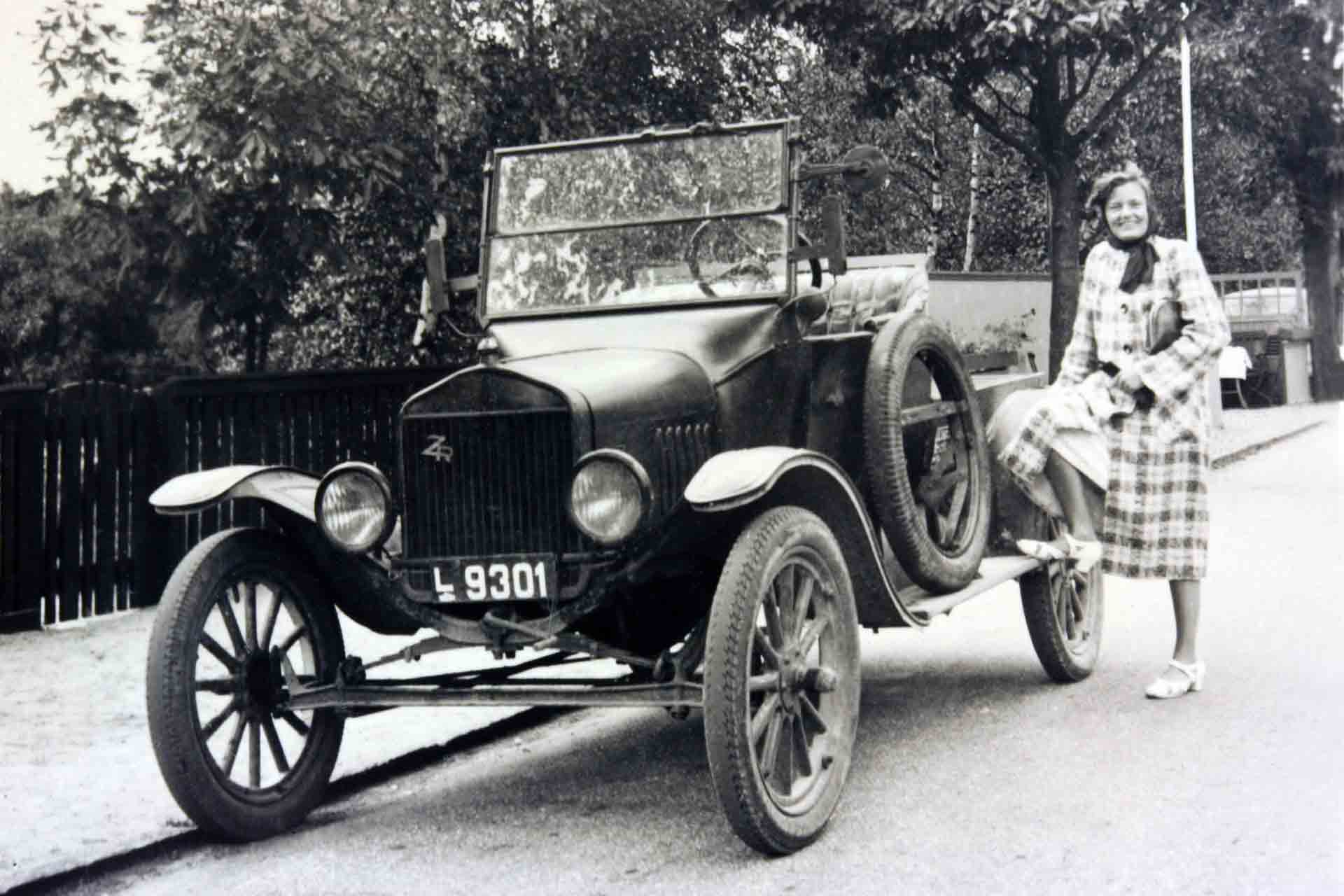

Soon, the seating arrangement that is common today is agreed upon, at the beginning of the 20th century. And cars still don’t have a roof, but gradually they do have a fabric top, and even in this respect, there are differences, from high-quality weather protection with insertable side windows (“American soft top”) to the miserable scrap of fabric through which the wind and weather whistle because it is open at the sides. While the first automobiles, identical to the carriages, are self-supporting constructions, the construction method common for the following 50 years emerge, according to which the body is bolted onto the chassis, i.e. both vehicle components only subsequently forme a unit. This is called frame construction. This has huge advantages. At that time, it is common for a vehicle manufacturer to supply only the chassis with the mechanics (engine, transmission, axles, wheels). The superstructure, i.e. the body, is built by external specialists on site. This makes for enormous individuality, which is why today, it is almost impossible to identify the very early classic cars unless you can see their radiator. The radiator is also made by the chassis manufacturer, and on the radiator (sometimes also on the wheel hubs), the manufacturer immortalizes himself with a lettering. At that time, there is an almost unmanageable selection of open cars, mostly two-door two-seaters (so-called runabouts) or four-door four- to seven-seaters (called touring cars). All of them are open. The first closed cars, or limousines, do not appear until around 1910. These are chauffeur-driven cars, because often, only the chauffeur sits under a fixed roof; the gentlemen have a convertible top on the rear seats. This type of body is called a landaulet. The last, generally known representatives of this genre are the Mercedes 600 Pullman and the Rolls-Royce Phantom VI: parade vehicles for statespeople who show themselves to the people. The Queen sat in a Landaulet, smiling benignly and waving her hand, as long as it didn’t rain during her state visit. The Pope, too, shows himself in an open car until it becomes too dangerous for him after the assassination attempt in May 1981. Since then, he has been sitting under a transparent, but armored dome in the popemobile.

[1] Ford’s classic Tin Lizzy, shown here as an open-top runabout, photographed near Rostock in 1928, according to the photo’s back label. (Photo: Archive afs)

[2] Typical small car: a Peugeot Bébé, 1913 to 1916. (Photo: Archive afs)

[3] The gentlemen drive open-top in a 1911 FN touring car. FN is Belgian and stands for Fabrication Nationale. (Photo: Archive afs)

[4] Open touring car, completely without a top: the Benz 25/45 hp from 1909 to 1912. (Photo: Archive afs)

[5] Two ladies and their chauffeur: a Renault 40 CV double torpedo from 1919. (Photo: Renault archive)

[6] From North Germany: the Hansa-Lloyd from Bremen, around 1914. (Photo: Archive afs)

[7] Something very rare: a LUC 8/22 hp two-seater from 1912, manufactured by Loeb & Co. in Berlin. (Photo: Archive afs)

The modern gentleman driver wants a roof over his head

In the 1920s, the enclosed body becomes increasingly popular, but is more expensive than an open touring car. Conservative people travel topless, and already at that time, people talk about experiencing nature. The speed of travel then is far more leisurely than it is today, and in fact, travelers in open cars get to see far more of their surroundings (including negative things) than those in sedans, where they are isolated. In the 1930s, the view changed. The “normal” car is a closed car, and increasingly, the bodies are made entirely of steel, no longer wooden frames covered with sheet metal. The open car stands for sportiness, the closed car for everyday suitability and comfort. This is also related to clothing. People who go to the opera or to board meetings dress differently than those who only have a convertible. He has to change his raincoat for his suit in the restroom. You do that once or twice. Then, you buy a closed car. At that time, a new genre is formed, the roadster.

[1] A sportsman presents himself and his car, an Opel 12/50 hp touring car with seven seats from 1927/28. (Photo: Archive afs)

[2] Small mishap: a Presto touring car from around 1920. (Photo: Archive afs)

[3] Two friendly couples go for a ride together in the 1919 Opel 14/38-hp four-seater. (Photo: Archive Matthias Schmidt)

[4] The automotive middle class in the 1930s: the Adler Trumpf. (Photo: Archive afs)

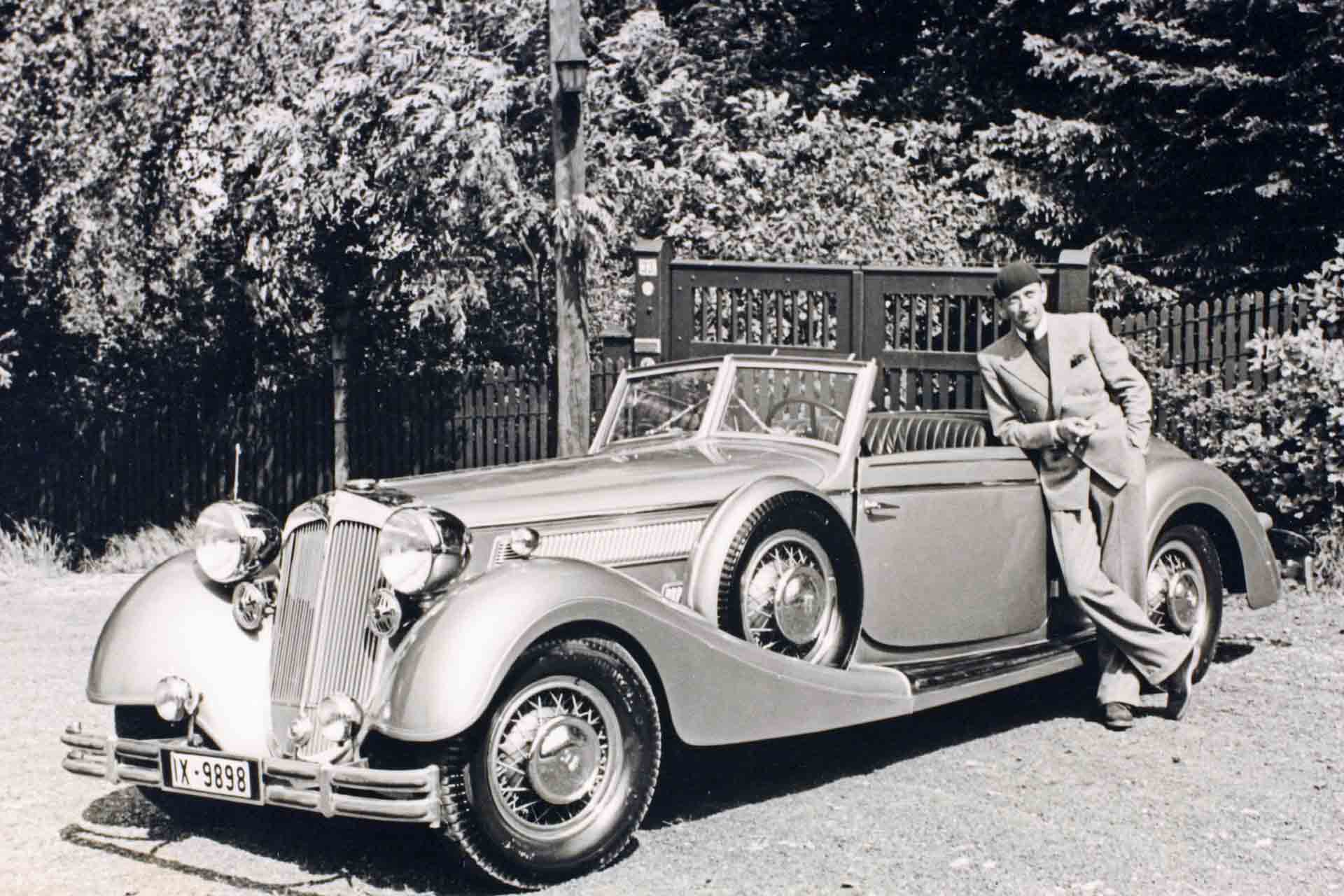

[5] Convertibles in the 1930s were sporty enthusiast cars, “pour le connoisseur”: a BMW 327 in front of the Wartburg in Eisenach, where it was manufactured. (Photo: Rainer Simons

)

[6] The ultimate kick back then: the 1937 Horch 853 Cabriolet with its body by Gläser. (Photo: Archive Matthias Braun)

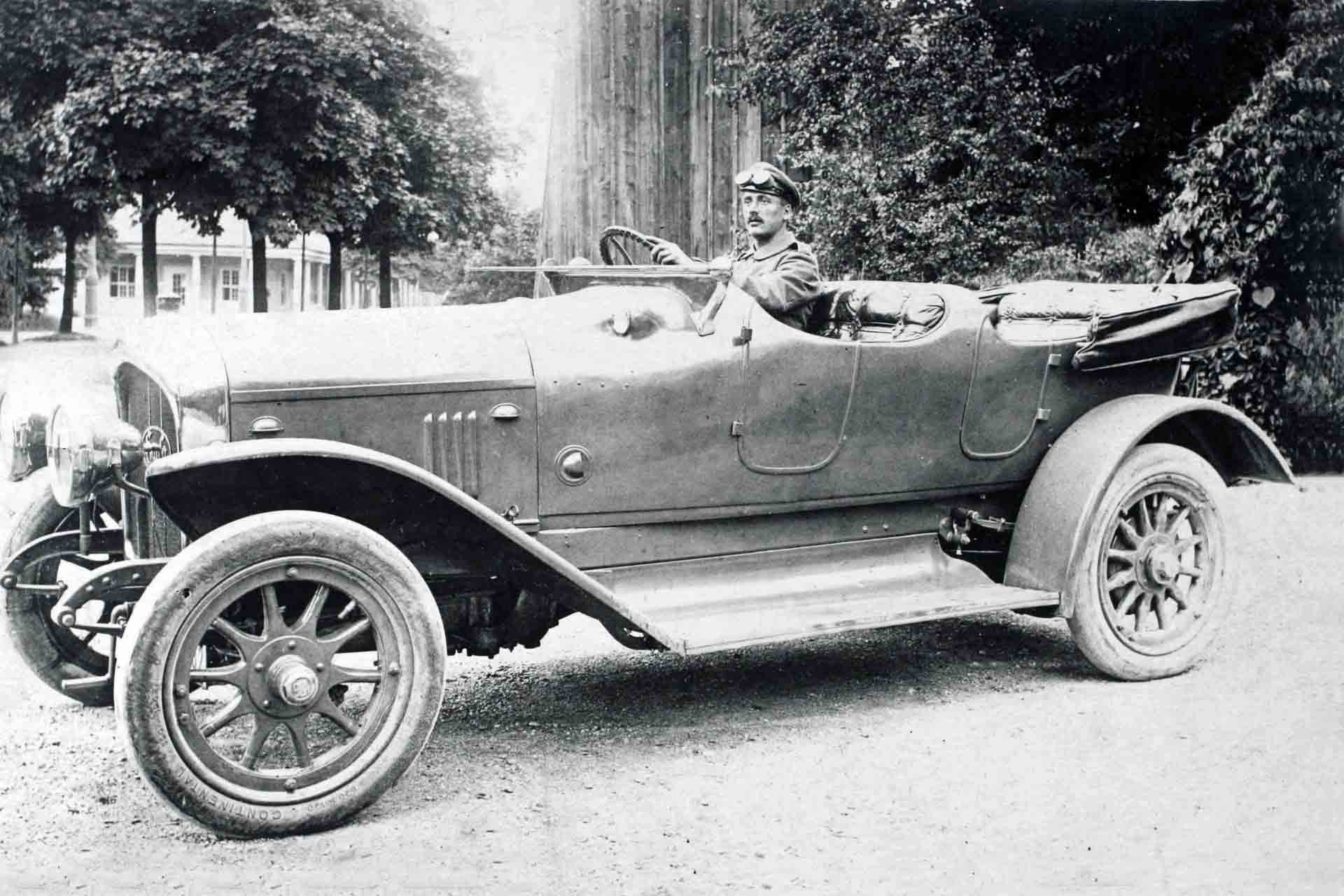

The small roadster for the “dandy”

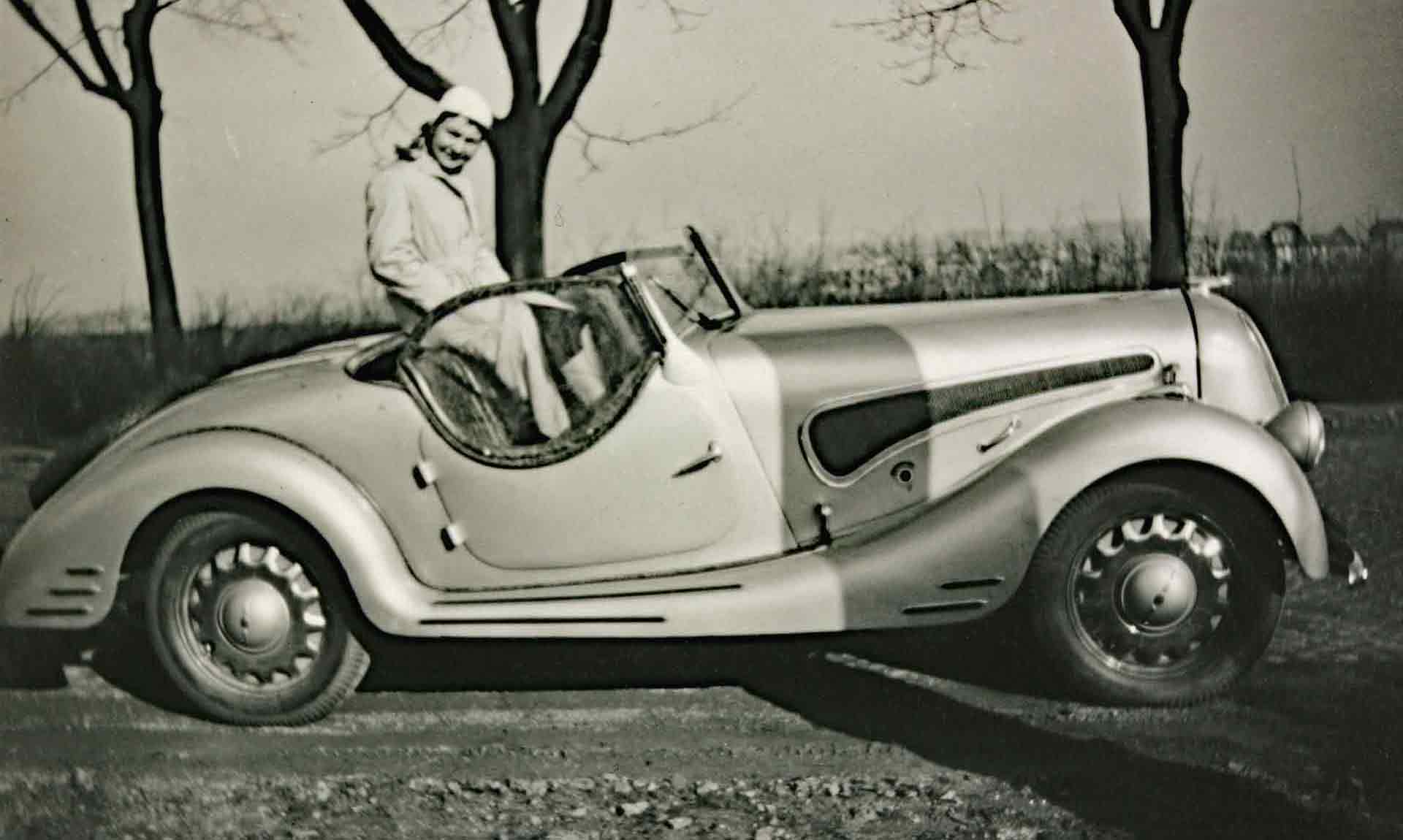

Roadster bodies are small with two seats, vehicles for young men with sporty appeal. Roadster bodies weigh little, and therefore quite decent performance is possible even with a moderate 30 hp under the hood. The “Stenz” (as they used to call in German what is now called a womanizer) quickly finds a lady with a crisp roadster, his lady of the heart, but the “little car” stands in the way of starting a family, of course. But it’s a hell of a lot of fun, and in the 1930s, a movement forms anyway that combines the fun of the automobile with sport. On a large scale, it’s all about reliability driving. And on a small, private scale, it’s really all about the fun of it, the joy of individual mobility. And just letting off steam.

[1] Ford Eifel Roadster with Deutsch body, vintage 1938/39, in pretty and chic two-tone paint. The doors with conventionally shaped upper edges ... (Photo: Archive afs)

[2] ... while the Ihle body manufacturer in Bruchsal gave its Eifel Roadster of the same vintage deep door cut-outs. This looks less elegant, but much sportier. Ihle’s style is based on racing and sports cars. After the war, Ihle sought its fortune in carousels and bumper cars for showpeople. (Photo: Archive afs)

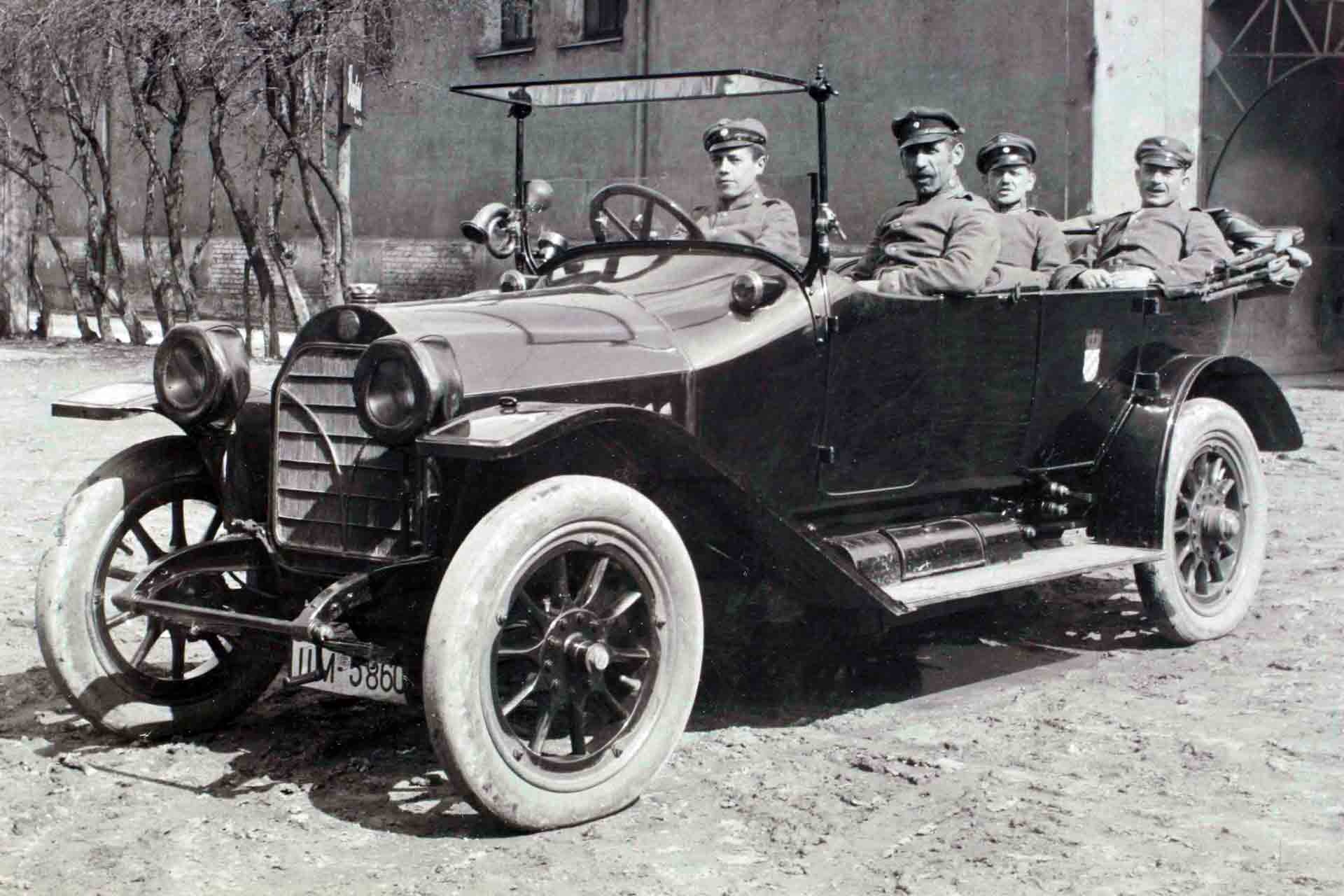

With a military ulterior motive:

off-road sporting events

On the one hand, the off-road sporting events serve the manufacturers to make their vehicles suitable for long distances, on the other hand, they train military drivers who can control a vehicle even under extreme conditions. The organizers of these reliability races (which can be considered as the beginning of rallies) are the Supreme National Sports Authority and the DDAC. That was the “German Automobile Club”. This was the name of the automobile clubs including the ADAC during the Nazi era. The off-road tests had a broad impact. Whereas motorsports had previously been a luxury sport, both socially and technically, which only wealthy people could indulge in with specially constructed bolides, the organized off-road tests become in a way more “democratic” – also for the manufacturers, because the rides are carried out with largely standard cars (namely with an open special body). Who joined the rally? They are privateers who can afford to buy a roadster built especially for this kind of tests. They are factory teams. And they are NSKK teams. NSKK is the abbreviation for National Socialist Motor Vehicle Corps. It’s a paramilitary sub-organization of the NSDAP. Members wear uniforms and have ranks. The participation of NSKK units in the cross-country tests gives this sport a political dimension, of course. To put it crassly, anyone who can successfully chase an off-road sports car around the track is an excellent driver under difficult conditions, even in wartime.

[1] The Opel “6” 2-liter off-road sports car at the Ostpreußenfahrt (East Prussia Rally) in April 1935. It had no electronic hill descent control and still managed to do it. Or just because of it. (Photo: Opel archive)

[2] The Ostpreußenfahrt in 1939 was one of the last rallies before war began. The Opel team chases up a steep slope on the Goldaper Berg (Góra Gołdapska), a moraine from the Ice Age, ideal for a cross-country drive. (Photo: Opel archive)

[3] Not only Opel participated: an Auto Union 1500 off-road sports car in action in 1937. (Photo: Audi archive)

[4] One of the few that survived: an Adler off-road sports car in the hands of an enthusiast. (Photo: afs)

The system change in car body design

After the war, the cards are completely reshuffled, including the automotive ones. Hardly any vehicle has a separate chassis anymore. Borgward sets the tone with the first new German post-war design, the Borgward Hansa 1500. With a few exceptions (such as the BMW 501/502), new developments have self-supporting all-steel bodies. The wooden body covered with sheet steel or imitation leather has had its day – only Borgward still builds the small Lloyd with a wooden body covered with imitation leather. Because the self-supporting body represents a unit in itself, it is constructed only in the most marketable versions. And these are sedans and station wagons, not convertibles. The open car becomes a mere connoisseur’s affair. Constructing an open body on the basis of an existing vehicle is a huge effort, virtually a new design. Because the roof is part of the structure, its omission means a profound intervention in the same, the calculated stability is gone. The bodies have to be extensively stiffened to be reasonably torsion-free and safe. Longitudinal stiffening is less of a problem: reinforcements along the door sills and/or the cardan tunnel are sufficient. The problem is transverse stiffening, because in this case, only the windshield frame is an option. No one thinks about the roll bar in the 1950s. Because of the self-supporting design, body builders are increasingly facing difficulties. Few body builders are able to specialize: ambulances and hearses, for example, are still the domain of a few specialized firms. Another way to survive is to partner with industry. For example, some have built cabriolets in series on behalf of major manufacturers, which are not suitable for large-scale assembly line production because of the quantities involved. Karmann in Osnabrück focuses on the Volkswagen Beetle convertible and the Karmann Ghia, Baur in Stuttgart cooperates with DKW and BMW, Karl Deutsch in Cologne supplies open Fords, and Autenrieth in Darmstadt provides topless Opels. Only Daimler-Benz and Porsche serve the convertible customers via assembly line. But these are very expensive vehicles.

[1] The convertible par excellence: the open Beetle in its first year of manufacture in 1949, bodywork by Karmann. (Photo: Archive Volkswagen)

[2] The Beetle’s big brother: the Porsche 356 Cabrio from the early fifties. (Photo: Archive afs)

[3] The alternative to the Beetle is the Ford humpback Taunus, also opened by Karmann. The picture shows a Taunus Spezial from 1950. (Foto: Archive afs)

[4] Parade vehicle for the wine queen: the Mercedes 220 W 187 Cabriolet from 1952. (Photo: Daimler Archive)

[5] The absolute dream car from the USA: the 1955 Ford Thunderbird, which is always associated with the film “American Graffiti”. (Photo: Archive Ford USA)

Convertible sedan:

neither fish nor fowl

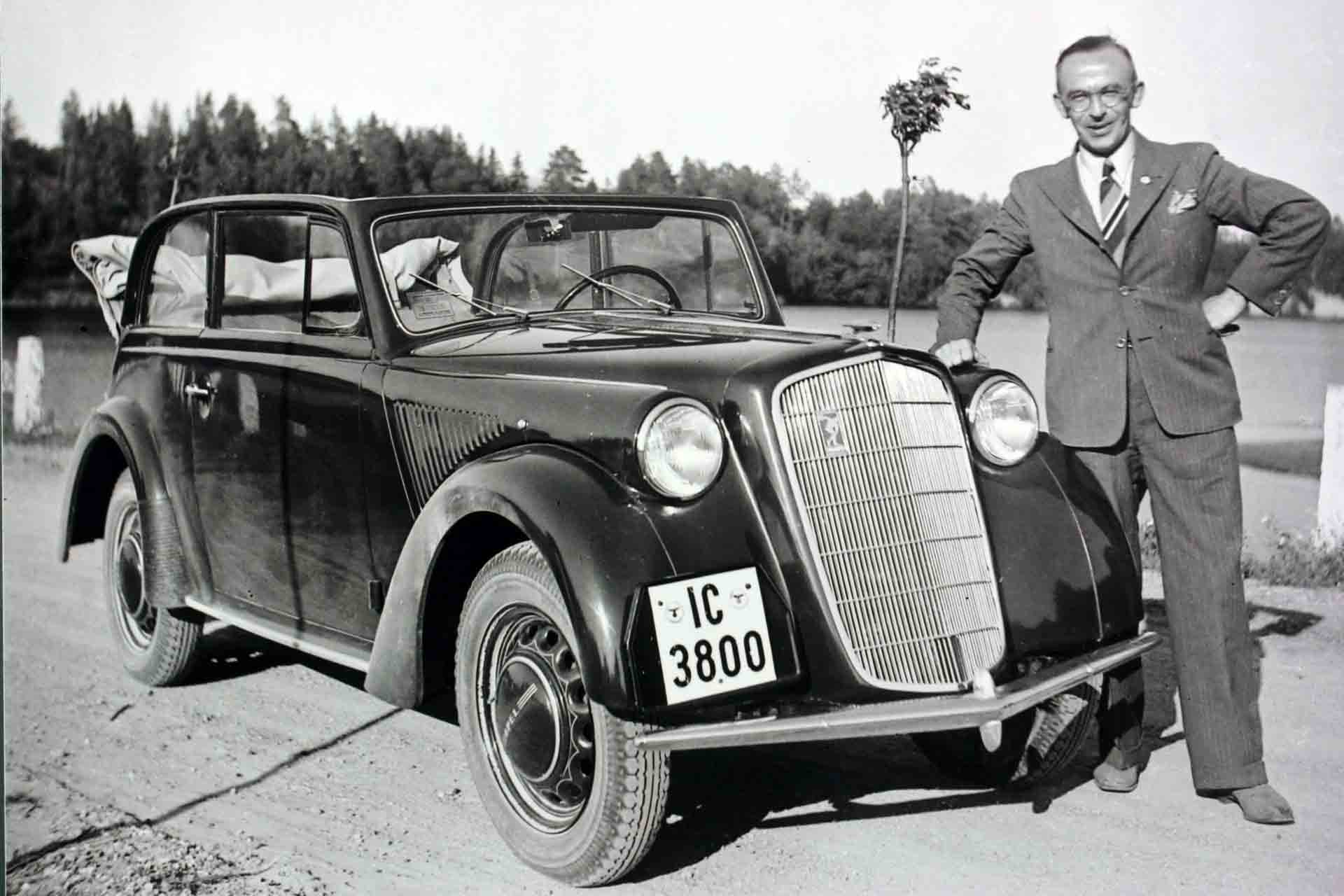

The convertible sedan could have been a compromise. It was well suited to self-supporting bodies, as Opel demonstrated as early as 1935 with the Olympia, the first self-supporting mass-produced car with an all-steel body. The cabriolet differs from the (full) convertible in that a steel frame is left around the window panes to reinforce the body structure. The feeling of openness is thus limited by the fact that the crew also looks out from the side as from a sedan, but just the same has a retractable roof. This body shape became established when the first all-steel bodies came into fashion in the mid-1930s. But customers did not accept it permanently; it was neither one thing nor the other, neither fish nor fowl. The last German convertible sedan was the Opel Rekord from 1953 to 1956, for this type of body was already a phase-out model after the war. Only one vehicle saved the convertible sedan type until the early 1990s: the Citroën 2CV, the “duck”. Today, it is enjoying a cheerful revival, for example with the Fiat 500.

[1] First to be released is the Olympia convertible sedan. Its purpose is to prove that the self-supporting body of the 1935 Olympia is stable. The sedan follows six months later. (Photo: Archive afs)

[2] The convertible sedan is a dying breed in the 1950s, and Opel is the only company to hold on to it: an Olympia Rekord ’53 with Swiss plates. (Photo: Wolfgang Diem)

[3] The Citroën 2CV is the convertible saloon par excellence. In this photo, it even serves as a wedding car for a duck-loving couple, seen in Dijon in the summer of 2009. (Photo: afs)

[1] Very high cuteness factor: the Renault 4CV called Cremeschnittchen in Germany as a convertible sedan with many contemporary chrome accessories. (Photo: Renault archive)

[2] One of the classics: the Fiat Nuova 500 with a completely retractable roof. (Photo: Fiat archive)

To be continued next week!

Text: Alexander F. Storz

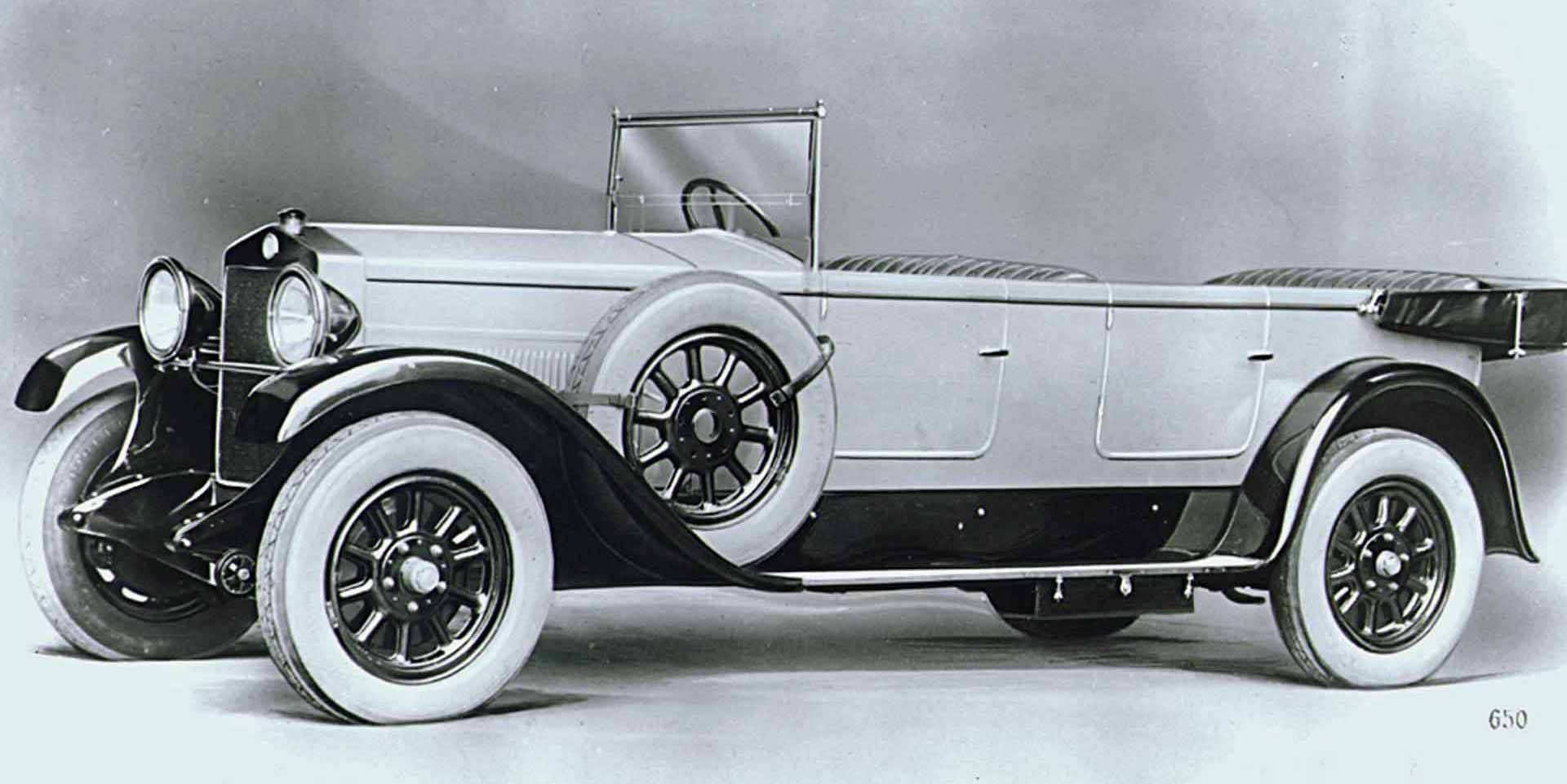

Cover photo: All the rage: whitewall tires on the Fiat 512 Torpedo, 1926 to 1928. (Fiat archive)

Oddities on open cars

The sunroof is nothing but a hole in the steel roof of a sedan or coupé. For a convertible fetishist, it is never an alternative.

Convertible drivers should wear headgear. UV exposure is underestimated because the wind from driving suggests the sun is not burning down from the sky.

Convertibles used to have no carpeting, only rubber mats, and not fabric, but leatherette upholstery. If need be, a convertible can be left open in the rain.

Definition convertible: vehicle that you can drive open in nice weather.

Definition roadster: vehicle that can be driven closed in bad weather if necessary.

Inspector Columbo drives his Peugeot 403 Cabriolet for a very long time (from 1968 until the end of the TV series in 2002). But the roof is never open.